Hmm...I'm sure if I'd tried a bit harder, I could have loaded more buzz words into that title!

I've been thinking a lot about searching the past few weeks. First, my DP students (grade 11) are just leaving the Pre-Search phase of their extended essays, and we're starting to talk about finding/managing sources. I'm also putting together a presentation on Information Dashboards that I hope will be selected for the EARCOS conference this spring.

If you read

Joyce or

Buffy at all, or just about any other library blogger/site, you know that "Curation" is the buzz word du jour. I pooh-poohed it for quite a while, thinking it was just a trendy name for what librarians (and researching students) have always done: collect sources and gather information. Then I had my own little

Eureka! moment: Collectors do just that: collect. Curators, however, collect content as the initial stage in telling a story about the material collected (as in the best museums). In other words, curators put what they collect into context.

I'm trying to fit that new way of thinking about search into the kinds of skills and tools I teach the students. I had a "take that" moment last Friday, when I asked a couple students if I could get screen shots of their Information Dashboards, Evernote collections, etc. for my presentation. They looked a bit shame-faced, then admitted they hadn't really used them, it had just been "easier" to load everything into a Word document. AARGGH!

I see that result partly as the nature of our workshops--I have to teach some of these things before the students are heavily into research, so I'm not there to reinforce using the skills/tools once they actually NEED them, and they fall back into old (bad?) habits. I need to address that problem directly with the students. Maybe give them time to brainstorm as a group just how they can use these tools productively.

More importantly, while I teach the tools and strategies, I don't think I've been teaching the "search mindset" epecially well.

Doug Johnson wrote a post today asking how professionals learn to search. The thing is, aside from a few tricks in the "advanced search" feature such as narrowing domains, etc. I don't do anything that different from the rest of our faculty--or students-- though I think of myself as a reasonably good searcher. What IS different is how I approach a search task, and knowing where to look for information, beyond "just Googling it."

In other words, searching today is multi-genre, and that's where curation, and curation tools, come in.

Gone are the days when I instructed students to "start with the books." I still encourage them to use them, of course, but depending on their topic (and my somewhat slim collection), that's often NOT the best place to start.

So I've decided to revamp how I approach teaching search strategies this year.

1)

It's Not About The Tools: I'll start with the appropriate search attitude. I've glossed on this with them--the usual "don't give up if it's not in the first page of results" sort of thing--but I need a more specific list of what good searching behavior looks like. More on this in later posts, but the point is, I need to emphasize this much more than I do. Being a tech-geek, I have too much tendency to focus on the tools, and this is a big mistake:

the tools are changing faster than we can learn to use them.

2)

Sometimes, It Is About the Tools: I used to think it was important to limit students' exposure to tools--that part of my job was determining which the best ones were for their task, and sharing only those. Now, I'm not so sure, and

this brilliant blog post cemented my thinking. Money quote:

Every place they go, people will be using a flood of differing devices. Every place they work people will be Skyping, Twittering, Chatting, Texting, working together in Google Docs, translating, searching for information and data, and building social networks. If they are not learning the best ways to do all this, your school is a failure, because your students will lack essential knowledge and social skills. (Key: If you can walk into a classroom and see a bunch of kids doing the same thing in the same way on the same device, you still have a 19th Century school.)

Thus, while we still need to winnow the list of resources down--students don't need 20 different curation tools--I need to offer the older students at least a variety of options, allowing them to choose the tools that best fit their needs and learning style.

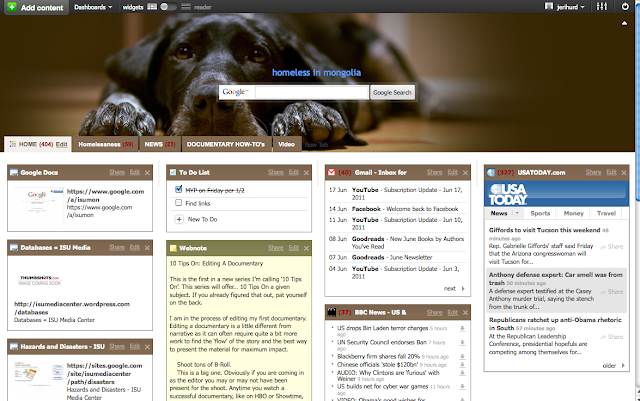

In the past, we

created dashboards with either iGoogle (my favorite) or NetVibes, then documented their research in EverNote and BibMe. Younger students use NoodleTools, but I wanted to wean them away from those subscription-based applications to apps they would available to them in the "real world."

In the Dashboard, their main page was personal, then they created tabs for their topics. I think I will still have them create a personal tab, and page in which to embed their paper (Google Docs), database feeds, etc. but now they will have the option to collect their other sources in Scoop.It or LiveBinder. I thought about Paper.li, but it looks like it only "plays" with Twitter and Facebook. Or am I missing something?

3)

The Shifting Nature of Authority: Ten years ago, would you ever have let a student cite a blog post in an academic paper? Now, I not only encourage them to, I think I'm going to "require" it. As part of their research, I want students to follow at least one expert on their topic, through both his/her blog and Twitter feed. I will also have them follow appropriate hashtags in Twitter for resources. Basically, I want to instill the idea of connectedness and collaboration into their searching by asking them to create a PLN, and we will talk about that as part of their research strategy/attitude.

This should also be a great point for discussing the shifting nature of authority in the digital world, and the increased need for triangulating information. I also think we need to get away from the idea that bias is bad. In the early days everything I read claimed the Web was bad because it was full of 'Opinion." The horror! The horror! It's more important to teach students to recognize opinion, acknowledge it as such, then determine where that opinion fits into the rest of their findings and their own learning.

5)

Beyond Web Portals: I used to talk to students about starting with web portals and content-specific search engines. It's still good for them to know about those, but they're almost a Web 1.0 construct, aren't they? In addition to searching Twitter, and Del.icio.us, students should also be searching the very tools they're using--

Scoop.It, Paper.li,

LiveBinder and even

Lib Guides for pre-curated content. They know to search YouTube and even Vimeo, but what about TeacherTube, iTunes U,

Big Think,

TED,

Information Is Beautiful and similar sites that tend not to come up high in the Google results? I think I'll create a list of site-specific links for them to include in their general search pattern.

4. We will continue to use EverNote as the storehouse for their notes, final list of resources, etc.

I'm going to create a new set of slides and handouts for this, which I will post.

In the meantime, please add your own thoughts, ideas or suggestions in the comments.

And here is the Scoop.It I created on

curation and tools, if you want to see what I've been reading.